It was a Friday in September, a month after I had moved to Amsterdam, the Netherlands. I had agreed to make challah and light candles with two girls from my Hebrew and Jewish studies program. Although neither were Jewish, I appreciated that they wanted to practice with me, and I was eager to make more friends. However, an hour before Shabbat, I found myself trapped in a heated debate with them as they derided Jews for their exclusivity and claimed they had more knowledge of Jewish texts than most Jews. I had this conversation before with one of the girls, and I had already gently tried to explain how problematic her statements were.

But time and time again, I found myself confronting students who thought that because they could read the Tanach in Hebrew and maybe had a Jewish grandparent, they had “earned” the right to be “honest,” or in most cases, antisemitic. In the apartment, as the girls began complaining about various aspects of Jewish culture, talking loudly over me, I suddenly felt very nervous.

They wanted to experience Jewish culture with me, but I was no longer needed. I was a Jew, in a Jewish studies program with her peers. But I was also surrounded by non-Jews claiming that their knowledge of Jewish scripture gave them a “right” to the religion, but seemed to have no respect for the community that they were so interested in studying.

I studied history during my undergraduate degree with a focus on Jewish and Middle Eastern history. Given the nature of my studies, many of my classes focused on Israel and Jewish history. Perhaps half of the students and most professors were Jewish in those classes. These bachelor level courses focused on a wide array of topics- Jews in American politics, Jews and immigration, Jewish world literature, ancient and modern Jewish civilizations, Jews in pop culture, the history of American Jewish women, and so on.

Of course, there were always classes on Israel, the Holocaust, and Jewish religious texts. Still, classes were certainly not limited to these topics. Further, I was able to engage with a wide range of active Jewish organizations. There was a plethora of Jewish student groups on campus and an abundance of programming and lectures about Jewish-related topics through the university.

Before starting my PhD in History, I decided to do a gap year of sorts. Since my semester abroad in Berlin was interrupted by the Covid pandemic, I decided I wanted to go back to Europe. So I enrolled in a MA program in Middle Eastern Studies with a Hebrew and Jewish Studies track and moved to Amsterdam, the Netherlands. I was surprised to find that out of the dozen or so students in my MA class, not only was I the only Jew, but I was surrounded by devote Christians.

The first “Jewish” organization I heard of on-campus (besides, of course, Chabad on Campus) was Sechel, which turned out to be less of a Jewish organization, at least the kind of Jewish organization I would find on my campus in the U.S., and more of an organization of “Hebrew studies students.”

This led to many interesting conversations and new perspectives. However, it also led to many uncomfortable situations. There were instances in my master’s class where Christians marvelled at how “strange” Jewish notions of the afterlife were. At one Sechel event, I had a student ask me when Jews stopped committing blood libel, and another student commented that I was “pretty for a Jew.” I found myself defending my religious practices to secular non-Jewish students who believed I was restricting myself and acting “rigid” because I (try to) keep Shabbat, a practice that no one had ever questioned before.

Make no mistake; I love my program. The professors are brilliant, the courses are engaging, and the department offers classes on various topics, from Jewish textual and intellectual traditions to cultural or material histories. However, UvA is the only university in Amsterdam and the Netherlands that still has a Jewish Studies department; other universities only have Hebrew studies. But what is the difference between Jewish and Hebrew studies, what is their history in Europe, and why is the latter so much more prevalent in the Netherlands than the former?

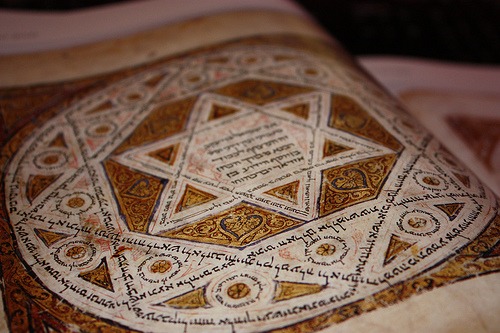

Many modern universities are rooted in Christian Hebraism, a movement of Christian scholars studying Jewish texts, beginning in the 16th century. Christian Hebraists were interested in reading from the Old Testament in Hebrew to borrow and adapt ideas to meet Christian cultural and religious needs. Christian Hebraists were interested in studying “pure” Judaism and tried, and often failed, to demarcate the “pure” scripture from “bad” Rabbinical Judaism. This movement saw the old Jewish texts as authentic but claimed that Jews misinterpreted their own scripture. Therefore Christian scholars needed Jews so that they could learn Hebrew and access Jewish manuscripts. This way, Christians could discover the texts’ “true” message.

Christian Hebraism was partly a philological project aimed to create a critical edition of the Hebrew Bible with different commentaries around the biblical verses. Further, it was a way for Christian scholars to assert Christian thought over Jewish tradition. However, some scholars argue that Christian Hebraism made Jewish texts known to non-Jews in a way respectful to the original iteration.

The growing popularity of this movement ensured Hebrew’s place alongside ancient Greek and Latin as a classical language in European universities. Some modern Hebrew/Jewish studies departments in universities are still based on Christian Hebraism, with a great deal of attention on philology and biblical interpretation. Apart from UvA, we see this at most universities in the Netherlands today.

So, what is Jewish Studies in Europe, how did it form, and how is it different from Christian Hebraism? The Haskalah movement developed in the 18th century when Jewish intellectuals (maskilim) spread over Europe, communicating through letters and shared journals (haMe’asef). The objective of haMe’asef was to write in “pure” Hebrew (biblical, not Rabbinic Hebrew). The maskilim were young (most were in their thirties) university-educated intellectuals. Dr. Shmuel Feiner describes their two-layered culture as partially Torah-oriented, partially European culture of the enlightenment.

Naphtali Herz Wessely (1725-1804), a contemporary of Moses Moses Mendelssohn (1729-86), published Words of Peace and Truth in 1782, perhaps the most important work among the German maskilim. He wrote that the whole Jewish school system should be reorganized. He wanted to bring Jewish society on par with non-Jewish society, turning the movement from religious to cultural.

He wrote of a “new Jew” whose complex identity would preserve Jewish religious culture and a sense of Jewish nationhood, alongside their European national identity. Haskalah was even brought outside of Europe by the Alliance Israélite Universelle. This Paris-based Jewish international quasi-colonialist organization funded schools based on Wessely’s model in an attempt to “civilize” the Jewish population in Western Asia and North Africa.

The Jewish enlightenment movement transformed into the Wissenschaft des Judentums in the early 19th century, Germany. The Wissenschaft was an attempt to develop a national histography that reconstructed Jewish history as a means of constructing a modern Jewish identity. The Wissenschaft was a product of European romanticism and empiricism that wanted to study the Jewish people in a different scientific way (empirical) and centered on Jewish culture and ethnicity instead of religion (romanticism).

Historicism was also crucial for this movement, particularly the notion that to understand a person from a specific time, you must understand their context and how history itself could become a source of nationalism and identity for a people. The Wissenschaft des Judentums saw a scholarly interpretation of Jewish history as a part of Jewish identity, where history could be detached from religion.

Christian Hebraism and the Wissenschaft grew into the modern academic disciplines we are familiar with today. Hebrew studies programs, to varying extents, are grounded in the Christian Hebraist tradition. According to Dr. Bart Wallet, the Wissenschaft has influenced the model of UvA’s Jewish studies department (to read more about Jewish Studies in the Netherlands, see Dr. Bart Wallet’s 2008 article, “The state of Jewish studies in the Netherlands, 1990-2008”).

While UvA’s Jewish Studies department, and their recent appointment of Dr. Wallet to full professorship, demonstrate that there is still a scholarly interest in Jewish culture and history in Amsterdam, the closure of Hebrew and Jewish studies programs at universities such as Leiden is foreboding.

So, what is the problem with the state of Jewish studies in the Netherlands? I cannot hope to give a thorough exploration of this question here. However, I want to highlight two issues. Whether a Christian Hebraist or a non-Jewish, Jewish studies student, people believe that their knowledge of Jewish scripture means they can comment on and deride the religion. And the second issue is that it is an endangered field here. The musealization and textualization of Judaism reduces it to its texts, and to history, which is far from the reality of Judaism as a living, ever-evolving religion.

The Netherlands is getting dangerously close to keeping the study of Jews confined to a study of old texts and the Holocaust. Of course, the study of Jewish textual traditions and the Holocaust is vital. However, it is also crucial to study Jewish contributions and accomplishments and the living tradition of Judaism. The Jewish community in the Netherlands has a long and vibrant history that should be celebrated, not diminished.